Two makers who find in skin a medium for revealing personal statements in ways that are simultaneously sophisticated and primal.

George Gustav Heye Center

Smithsonian National Museum

of the American Indian

New York, NY

Part One: Sonya Kelliher-Combs

and Nadia Myre

Mar. 6 - Aug. 1, 2010

Common Thread, 2010, reindeer and sheep rawhide.

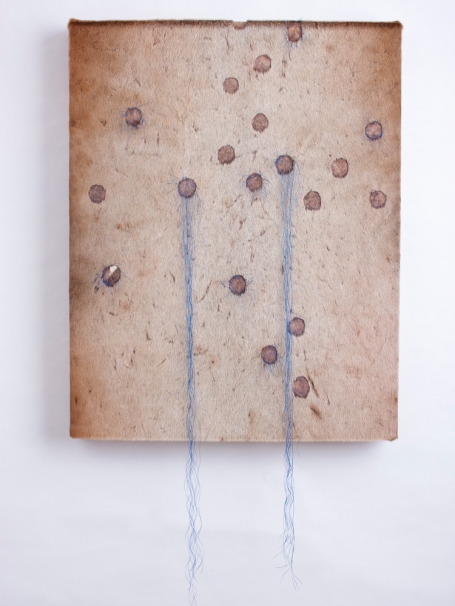

Sea Lion Brand with Blue, 2009, sea lion skin/fur, nylon thread, 29.71 x 23.79 in. Photo Kevin G. Smith

Small Secrets, 2009, detail, walrus stomach, human hair, mixed metals, dimensions variable. Photo Kevin G. Smith

Salmon Walrus Family Portrait, 2009-10,

acrylic polymer, walrus stomach, reindeer fur, mixed media, 67.33 x&&160; 39.75 in. Photo Kevin G. Smith

cut and sewn canvases, each 10 x 10 x 2 in., stories on paper.

Photo &&169;Nadia Myre, licensed by CARCC, Ontario and VAGA, New York.

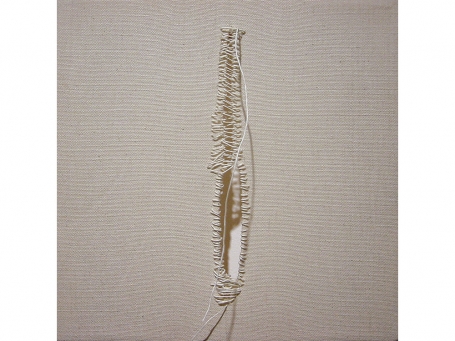

The Scar Project, 2005-present, detail of single canvas, 10 x 10 x 2 in. Photo &&169;Nadia Myre, licensed by CARCC, Ontario and VAGA, New York.

Animal skins-hides-have played an important role in traditional Native American culture and identity, and the National Museum of the American Indian has regularly exhibited such venerable objects as beaded deerskin garments and paintings on buffalo hide. But this two-part exhibition, curated by Kathleen Ash-Milby, is not about tradition. Contemporary artists who are known in the art world but retain strong ties to their Native communities were invited to address skin as an actual art material and as a vehicle for comments on a range of social issues. The first part highlights two makers known for multimedia work who find in skin or its representation a medium for revealing personal statements in ways that are simultaneously sophisticated and primal.

Alaskan-born Sonya Kelliher-Combs (Inupiaq/Athabascan) combines organic and synthetic materials in works that convey intimacy in their tactility, yet are baffling in their hidden meanings. In the series Walrus Family Portraits, she layers ghostly pouch-shaped walrus stomachs within a medium of acrylic polymer, augmenting the texture with nylon threads, glass beads and reindeer fur. The surface is mottled and bumpy; the colors enhance the play of light. The hanging threads remind one of fur trim on a parka.

The pouch form reappears three-dimensionally in Kelliher-Combs's wall installation Small Secrets, a row of diminutive fingertip-shaped containers made of walrus stomach bristling with human hair, glass beads and nylon thread. They resemble delicate empty shells that once enclosed a form or substance. Common Thread, a similar but larger installation, comprises three rows of pouches, stitched from reindeer and sheep rawhide rather than stomach membrane.

Even more redolent of her Alaska heritage is her series Brand, in which Kelliher-Combs has brought together walrus stomach, seal intestines, reindeer, polar bear, elk and moose fur, seal skin and the like, as well as acrylic polymer, nylon thread, paper and cotton to create 15 panels. She aggressively "processes" these skins, stitching them or branding them with circular "pores" or piercing them with metal grommets, the last suggesting human domination of nature. This work is about "making things our own, ownership and control," she has said.

Unlike Kelliher-Combs, Nadia Myre (Anishinaabe), an artist living in Montreal, does not use organic materials to comment on skin. Her preoccupation is scars, and more than half of her part of the exhibit is devoted to The Scar Project, a communal work. Since 2005, Myre has held workshops in which she provides participants with 10-inch-square canvases and invites them to render their own scars-bodily or mental-by cutting and "suturing" the raw cloth. The 240 canvases (out of some 500 in the project) are arranged on both sides of a large gallery. Although much of the work seemed primitive as sewing, the cumulative effect is powerful and visually harmonious because of the nearly monochromatic effect-beige, white and light brown threads against the off-white canvas. What might have been presented as bloody wounds or disfiguring stitches are abstracted, even aestheticized, by the subtle colors. Another work, Landscape of Sorrow, also of canvas and cotton thread but done by Myre alone, is a grouping of six horizontal canvases, each depicting a long scar through a slit in the canvas "healed" by irregular stitching.

The theme continues in Scarscapes, several small rectangles made from glass beads and cotton thread, each with the central image of a black scar against a white background. On the wall nearby are greatly enlarged photographic images of details of the beaded works. Such pieces indicate Myre's pride in her Native heritage and its beading tradition. Such pride is conveyed in a more visceral way in Inkanatatation, a short digital video documenting the artist having her arm tattooed in a design of three red feathers. It is meant to suggest an alteration in the Canadian flag-the replacement of the maple leaf with feathers-as a way of honoring the country's aboriginal peoples. With its mingling of red ink and blood, this film returns the "ouch" factor to what has been presented at a remove in Myre's scar installations, and reminds the viewer that skin, real skin, is the subject of this exhibition.

Part Two of "Hide" will be at the museum Sept. 4, 2010 - Jan. 16, 2011. The catalog is $23.95.